Resilience and Wellbeing

A can of Coke and a U2 song: Why the way in which you help someone matters

Just like in physical first aid, there is an evidence-based set of practical skills that can be applied when offering assistance to someone experiencing a mental health issue. It is called Mental Health First Aid.

by Catherine Stokes, BA LL.B (Hons.) Executive Director, The College of Law (WA) and Accredited Mental Health First Aid Instructor

The article was first published in the Law Society’s Brief journal in October 2021

Want to know more? view our programs

published 13/12/2021

Note: this article contains an account of a car accident and reference to a panic attack.

Many years ago as a young driver I was behind the wheel, heading south on a country road. My parents were passengers in the car. Approaching a bend, we saw a cloud of dust appear ahead. My mum was in the front seat and urged me to slow down, as we didn’t know what was ahead. We rounded the bend and there was a car ahead of us on the left-hand side of the road. The car was upside down on its roof. We pulled in behind the upturned car and got out. As we moved towards the car, the engine was running and the wheels were still spinning. The driver was strapped in the car upside down. I reached inside and turned off the ignition. Another vehicle stopped and together with these helpful strangers, we applied physical first aid.

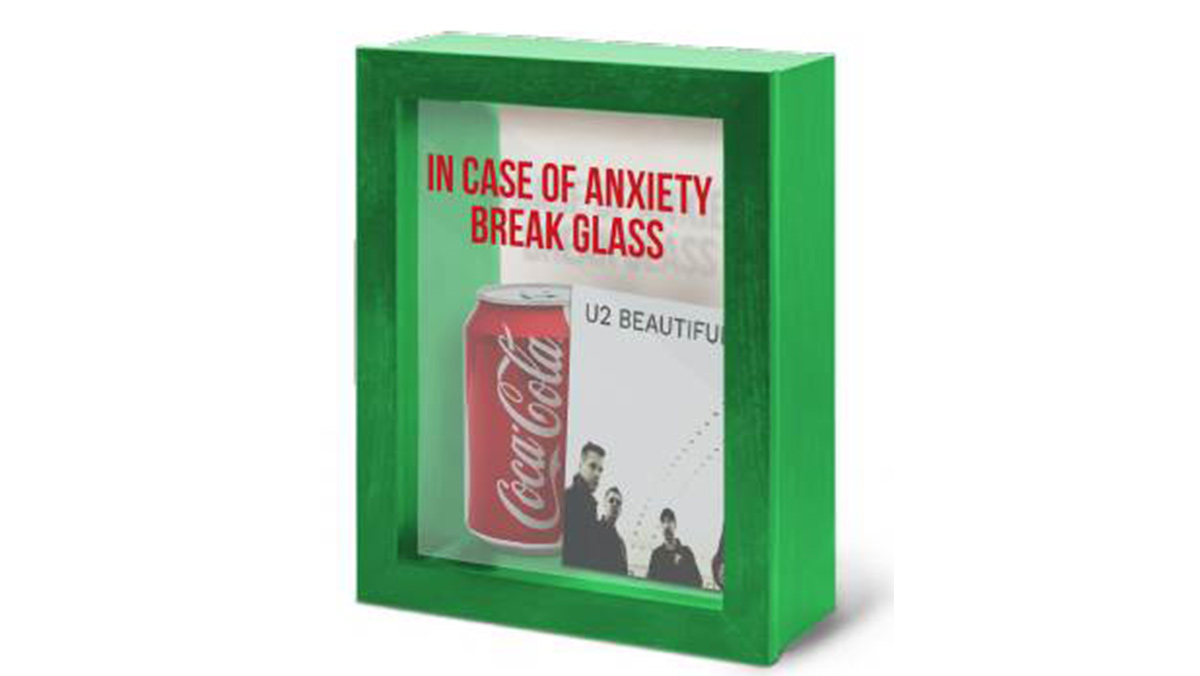

A few minutes later, the injured driver of the upturned car was seated on the ground under a tree as we waited for help to arrive. As time went on, the well-meaning strangers felt very strongly that the injured driver should have a can of Coke, which they pressed into her hand. They were insistent that the sugar would help and the caffeine would assist her to stay conscious. Now I have nothing against Coca Cola. I was however aware that soft drinks are not an evidence-based first aid measure for someone who had just been in a car accident, was complaining of abdominal pain and/or may require surgery shortly.

Fast forward many years and I am standing in a kitchenette having a conversation with a person whom I will call Emily. Emily was upset. She was pale and shaking and had just indicated to me that she thought she was having a panic attack. She spoke about her lived experience of anxiety and a recent trauma involving a close family member. Unfortunately, there was not a private place to have this conversation and we were overheard by someone nearby.

This well-meaning stranger was clearly affected by the distress and the experiences that Emily was describing and urgently pressed a business card into Emily’s hand for a very niche form of “support” that they insisted would help her. The well-meaning stranger then gestured to the sunshine and water views outside the window and said “Stop worrying, just look outside, can’t you see it’s a beautiful day!” Now I have nothing against observing that it is a beautiful day, or against U2, whose song of that name was one of their biggest hits. I was however aware that those sorts of phrases and the particular “support” on the business card were (and still are) not an evidence-based first aid measure for someone suffering from anxiety and a possible panic attack.

Looking back on the more recent instance it occurred to me that the well-meaning stranger was offering the mental health first aid equivalent of a can of Coke. I want to make it clear, in both cases the well-meaning strangers wanted to help and had suggested action which they genuinely believed would assist. However, there are compelling reasons why we train people in first aid.

1. There are established evidence-based best practices

There are helpful and unhelpful ways to respond to someone in need of assistance, and a substantial body of peer-reviewed, that first aiders assist, with respect to both physical and mental health first aid.

Just like in physical first aid, there is an evidence-based set of practical skills that can be applied when offering assistance to someone experiencing a mental health issue. It is called Mental Health First Aid.

Mental health first aid is an evidence-based1 training course which has been established in Australia for 21 years. It is the only internationally recognised, evidence-based, anti-stigma mental health training course for workplaces.2 The MHFA course is characterised by practical skills training, backed by academic research on the course content3 and efficacy4.

The course gives attendees the skills and confidence to have supportive conversations with their colleagues and peers and help guide them to professional help if needed. Specifically, mental health first aid courses teach participants how to provide initial help to a person who is developing a mental health problem, experiencing a worsening of an existing mental health problem or is in a mental health crisis. The first aid is given until appropriate professional help is received, or the crisis resolves.

2. Boundaries are important

Over the past six years during which I have trained people to deliver mental health first aid to colleagues in the legal profession, friends and family, the parallels between physical first aid and mental health first aid are clear to me. Not only does drinking soft drink not feature in any of the evidence-based responses, both forms of first aid aim to provide assistance to a person as a first responder until appropriate professional help is received.

In both physical and mental health first aid, the first aider does not diagnose or treat the person requiring assistance. Instead, their role is to assess and provide assistance in accordance with evidence-based best practice for first aid.

In the same way that regular first aid courses do not teach a person to become a paramedic, a Mental Health First Aid course does not teach attendees to become counsellors or take on the role of an appropriate health professional. Just as you would not perform emergency surgery as a first responder, a mental health first aider does not diagnose or treat a mental health problem. A mental health first aid officer in the workplace (for example) is not a substitute for professional support services such as a general practitioner, psychologist or EAP or a mediation or dispute resolution mechanism.

3. We know that some ways of helping work better than others

Colleagues, friends and family can assist by informing themselves about mental illness and what the person is experiencing, as well as providing the kinds of support you would provide to someone experiencing a physical illness. There is now a wealth of information available on the signs and symptoms of common mental illnesses and the types of support which can be of assistance. You can inform yourself from credible sources such as Beyond Blue5, which publishes free comprehensive guides on “What Works for Depression” and “What Works for Anxiety”. These guides cover a whole range of forms of assistance, with information on what interventions help, those which have no clear evidentiary basis and those which might in fact be harmful.6

There has been a comprehensive body of research over 20 years to evaluate the efficacy of mental health first aid. These evaluations consistently show that mental health first aid training is associated with:

- improved knowledge of health problems and their treatments;

- knowledge of appropriate first aid strategies; and

- willingness and confidence to provide first aid to individuals with mental illness, benefits which are maintained over time.7

Some studies have also shown improved mental health in those who attend the training, decreases in stigmatising attitudes and increases in the amount and type of support provided to others.

Offering assistance

Given most mental health problems develop slowly, and that we spend so much of our time at work, it is likely that a co-worker with appropriate knowledge and skills would be able to detect the early signs and symptoms of a developing mental health problem. They would also be in a good position to offer help and support a co-worker whilst they seek professional assistance.8 Research indicates that people are more likely to seek appropriate professional help if someone close to them suggests it.9 We also know that people suffering from depression, for example, will experience faster recovery from symptoms if they feel supported by those around them.10

There are some clear differences between mental health first aid and physical first aid. I never saw the driver of the car again. I hope that she was all right. As is often the case with physical first aid, I had no further involvement in assisting her once the ambulance arrived. By contrast, I had a chance to follow up with Emily again and ask how she was going. In mental health first aid, you may become involved in assisting that person at an earlier stage, as a mental health problem develops and in some cases continue to provide that assistance over a longer period of time. In my experience, I have applied my mental health first aid skills far more often than my training in physical first aid.

Conclusion

Seven years ago, Tim Marney, the former WA Mental Health Commissioner expressed a hope that it would become normal to have on any workplace noticeboard the name of the first aid officer and next to that, the name of the mental health first aid officer.11 This article covers just a few of the many reasons why we should continue to ensure that both physical and mental health first aiders are trained and available to assist in high risk environments, including our legal workplaces.

End notes

1 For example, MHFA Training has been recognised as an evidenced-based practice by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), an agency of the US Department of Health and Human Services

2 Szeto AC, Dobson KS. Reducing the stigma of mental disorders at work: A review of current workplace antistigma intervention programs. Applied and Preventive Psychology, 2010.

3 See for example Bovopoulos, N., Jorm, A.F., Bond, K.S. et al. Providing mental health first aid in the workplace: a Delphi consensus study. BMC Psychol 4, 41 (2016) and other research informing the MHFA curriculum cited here: https://mhfa.com.au/research/mhfa-australiacourse-development

4 See peer-reviewed research cited at https://mhfa.com.au/research/mhfa-course-evaluations

5 https://www.beyondblue.org.au

6 https://www.beyondblue.org.au/docs/default-source/resources/484150_0220_bl0762_acc.pdf

7 Ibid, at 4

8 Mental Health First Aid Australia. Providing mental health first aid to a co-worker. Melbourne: Mental Health First Aid Australia; 2016.

9 Kitchener B., Jorm A. and Kelly C. (2019) Mental Health First Aid Manual 4th Edition.

10 Keitner GI et al. Role of the Family in Recovery and Major Depression. American Journal of Psychiatry 1995; 152:1002-8, cited in Kitchener B., Jorm A. and Kelly C. (2019) Mental Health First Aid Manual 4th Edition.

11 Tim Marney, WA Mental Health Commissioner quoted by Aleisha Orr “WA businesses encouraged to appoint mental health officers” WA Today 10 October 2014